Romanesque architecture is an architectural style that appeared in Europe around the year 1000 and was replaced by Gothic in the second third of the 13th century. In Latvia, only the Late Romanesque style can be found, which was introduced with the advent of stone architecture in the early 13th century. Romanesque style was gradually replaced by Gothic in Livonian stone buildings in the middle and second half of the same century, slightly later than in Western Europe. The name Romanesque style is a direct reference to the architecture of ancient Rome, from which European architects of the 11th-13th centuries adopted semi-circular arches, massive pillars and round columns as well as semi-cylindrical vaults to cover rooms and thick masonry walls. Like other architectural styles, Romanesque is most fully expressed in church buildings. The imposing Romanesque cathedrals symbolised the omnipotence of God and the power of Christianity, so in sacred buildings the expressive language of Romanesque forms is in many cases decorative and an-end-in-itself. In contrast, in the great secular buildings of medieval stone castles, the architect had to think at first of the practical use and defence of the building. That is why the decorative features of Romanesque style are less common in the castle architecture.

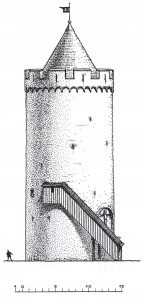

The Main Tower of the Turaida Castle in the 13th century. Reconstruction drawing by architect Gunārs Jansons – a view from the castle yard (2007)

The only Romanesque structure in the Turaida Castle that can be fully seen above ground, which dates back to the 13th century, is the Main Tower - the Bergfried or Berchfrit, which is more than 30 metres high. The origin of the name is not entirely clear, but it is sometimes translated as 'peacekeeper' (German: bergen - 'to secure' + Frieden - 'peace'). In Western European castles, the 12th and 13th centuries were the heyday of the great main towers, the bergfrieds, but in the 14th century they were less common. Such a tower had to be high enough to be used as a lookout. The bergfried was usually one of the first structures to be built in a castle, before high defensive walls around the courtyard and other fortifications were erected. The main tower stood apart from the other buildings and was not connected to them.

If the bergfried was built on the side from which the attack came, this strong tower served as a shield for the rest of the castle. The high bergfried was the last fortification for defenders and a refuge for all inhabitants of the castle in case of temporary danger. Its entrance was located at least at the second-floor level, so that attackers could not enter the tower so easily. If a horde of pillagers approached and the castle had few inhabitants, they would quickly climb up to the second floor of the bergfried by a wooden ladder, which could be easily demolished, and stay there for several hours until the enemy had disappeared.

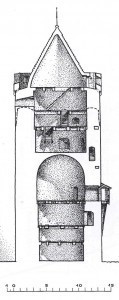

The Main Tower of the Turaida Castle in the 13th century. Reconstruction drawing by architect Gunārs Jansons. Cross-section (2007)

The bergfried's accentuated heavy walls are conforming to the Romanesque style - the thickness of the walls on the north side of the lower floor reaches 3.7 metres. Among all buildings in Turaida, only the tall Main Tower is made of particularly large medieval bricks - 33 centimetres long. The Romanesque and 13th-century construction is characterized by the use of Wendish bond (monk bond, a variant of Flemish bond in Europe) - a rhythmic layering of bricks in which two stretchers or longitudinally laid bricks are followed by one header or perpend in each course. The semi-spherical dome vault on the fourth floor is also heavy. It was, however, renovated when the tower was restored - 60 years ago, using traces of the vaulting preserved in the walls. A decorative element conforming to the Romanesque style is the semi-circular arcade, which can be seen in the corona of the tower's outer wall under the roof. Unfortunately, the arcade has not been preserved since the Middle Ages. It has been completely restored, as the top of the tower had crumbled away over the centuries. However, similar arcades can be seen at the upper edge of begfrieds in many other European countries.

Passive defence is the key feature of Romanesque fortifications. This means that the height of the defensive walls and towers had to be so high that it would be difficult for an enemy to overcome them by climbing up the ladders. Similarly, the walls of the castle had to be so thick that it would be impossible for an enemy to break a hole in them. However, some active defences were also installed in the castles. These were usually merlons at the top of the walls, which along with crenels formed a crenellated top (battlement) of the outer wall.The merlon provided cover for an archer standing on the guards walkway, who shot arrows at the enemy through the crenels made between the merlons or through narrow vertical loopholes made in merlons. It is possible that the top of the Turaida bergfried was also crenellated, as shown in the reconstruction drawing made by architect Gunārs Jansons.

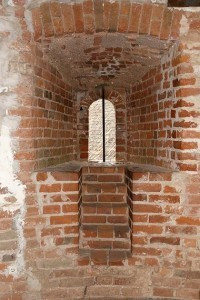

As elsewhere, also in Turaida there are few openings in the walls of the main tower. On the fourth floor, where the fire in the fireplace made the stay more pleasant during the chilly weather, there is a window with a Romanesque semi-circular lintel, with seats on both sides and a view to Kubesele. Other apertures in the bergfried walls are a few narrow openings - small rectangular windows with sloping side walls that extend inwards.They were useful for lighting stairways, ventilating indoor areas and for observation, because it was difficult to use them for shooting. The location of the narrow openings in the main tower of Turaida were inefficient and played little role in defending the castle with firearms.

Passive protection required that openings in the outer walls of the towers would be built no lower than the second floor and as narrow as possible, otherwise they would endanger inhabitants of the castle themselves. In the openings on the lower floors, the attackers could easily hit with arrows, stones and burning objects, also break the edges of the openings and climb through them in the inner room. This has been taken into consideration in the case of Turaida, but there are also few openings in the walls on the upper floors of the tower. They could not be used to oversee the surroundings and, if necessary, to fire in all directions in the nearest area around the tower. On the one hand, this reduced the chance that enemy arrows would hit the inhabitants of the castle through the openings. It was important for passive defence. On the other hand, it made it difficult to defend the castle actively. In addition, the small openings were built into a wall several metres thick and were almost waist-high. A man with a crossbow would not be able to get close to the opening, not to mention bending over. Shooting from a distance made it difficult to hit the target. Therefore, it can only be concluded that the small openings in the walls of the Turaida bergfried were rarely used for shooting and the arrows fired from them could not have contributed significantly to the defence of the tower.

To make the shooting through the opening (loop-hole) more meaningful, a deep niche had to be constructed at the thickness of the wall and the narrow vertical loop-hole opening had to be almost at the height of adult man. Such a loop-hole sometimes had an additional small horizontal extension at the top edge or in the middle for better visibility and aiming.However, arrows shoot through the loop-hole by crossbowman hit only a small area quite far from the castle walls. The strip of land outside the wall, which the defenders of the castle could not reach with their weapons from the upper floors, was called the "blind spot" (German: der tote Winkel).

This was a weak point in the defence of Romanesque and early Gothic castles. Once some of the attackers had crossed the strip unharmed, where the arrows fired by the defenders fell, the enemies at the foot of the fortification could break the walls or gates easily, or dig under the foundations. However, mostly the castle was besieged and its inhabitants starved until they surrendered. Another way to get into the castle was if the enemy found a traitor among the castle servants and bribed him to secretly open the gates. Otherwise, before the invention of cannons, it was difficult to conquer a strong stone castle.

Turaida bergfried - the main tower, built in the Romanesque style, has survived for 800 years. At that time, it was an important passive defence building where the inhabitants could temporarily find refuge in case of danger. Throughout its existence, the tower's great height ensured a long-distance view of the surrounding area, so it was used as an observation post by the guards. In addition, the mighty red brick tower rose high above the treetops, becoming a symbol of the castle, a sign of the bishop's authority and an important landmark for travellers by land and water. Today, the ancient tower offers visitors an unforgettable view over the ancient Gauja valley in bright sunlit summer mornings, in autumn mist and in the whiteness of winter snow.

Dr.hist., Ieva Ose Chief specialist of the Turaida Museum Reserve